Our goal is to create a beloved community, and this will require a qualitative change in our souls as well as a quantitative change in our lives.

— Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. wrote in one of his first published articles that the purpose of the Montgomery bus boycott, “is reconciliation and redemption . . . the creation of the beloved community.” In 1957, writing in the newsletter of the newly formed Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), King described the purpose and goal of that organization as follows: “The ultimate aim of SCLC is to foster and create the ‘beloved community’. Our ultimate goal is genuine intergroup and interpersonal living….” And in his last book, he declared: “Our loyalties must transcend our race, our tribe, our class, and our nation.”

I’ve been thinking a lot about the concept of a beloved community in the time of COVID-19. So much has happened over this last year, personally and globally, with the pandemic radically realigning our individual and collective priorities and possibilities. The pandemic has threatened the gains of many social movements. So, what are we to do?

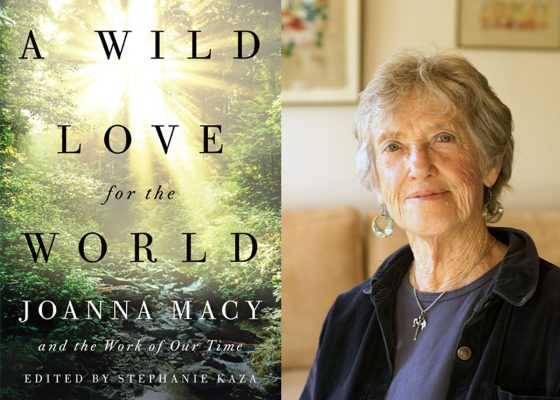

The eco-philosopher, Joanna Macy, who has led such powerful despair and empowerment work, said in an online session titled “Pandemic as Practice,” “COVID is acting as the most amazing pulling away of ignorance and avoidance of things in our planetary culture . . . to get to what is needed for justice, love, equal access to health for all, and healing for the world.”

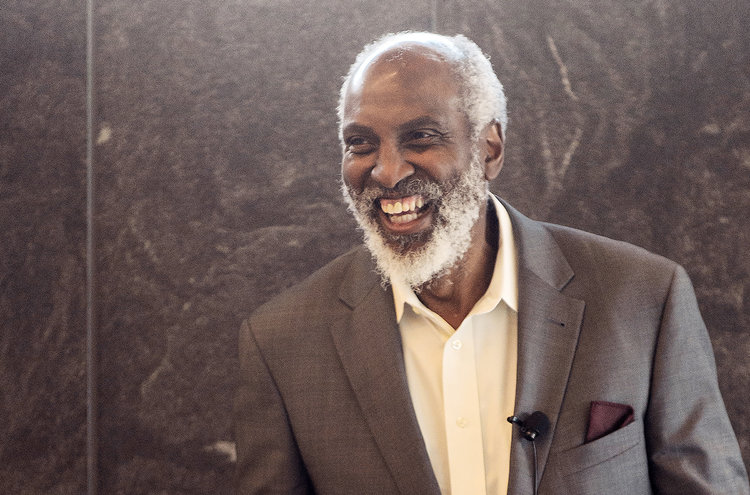

As activist-scholar John A. Powell said, “When societies experience big and rapid change, a frequent response is for people to narrowly define who qualifies as a full member of society.”

The gender dimensions of COVID-19 have meant that many women remain the “other”, often denied their rights and sense of belonging. There are a growing number of cases of women, especially black and brown women, who have experienced having their COVID symptoms dismissed as psychological, as a form of gaslighting. Domestic violence has increased dramatically, with many women trapped in homes with their perpetrators. And perpetrators are adapting to the pandemic too, employing greater surveillance of their victims’ internet history and phones. In some countries, women’s jobs are being wiped out at twice the rate of men’s because the worst-hit industries are female-dominated, and mothers are shouldering the burden of helping children learn at home.

The language of “building back better” after the pandemic doesn’t go to the heart of what’s needed. There must be attention to pay equity, equity in caregiving, and the level of funds and political will required to end gender-based violence. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 35 percent of women worldwide have experienced either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence, and yet paltry resources have been committed to eliminating gender-based violence. In places like Mauritania, girls are still being force-fed by women at fat farms to be desirable to men and married off like livestock or slaves. While in Papua New Guinea, women’s bodies are collateral in tribal disputes near mine sites.

The economic and social COVID recovery plan can’t be about tinkering around the edges and drawing on traditional responses to economic crises i.e. prioritizing male-led industries such as construction. Rather there needs to be new investment in health, education, and service industries that have been decimated by the demands of the pandemic and that employ a predominantly female workforce. The approach must be about a reimagined world and a radical realignment of resources, power, structures, and norms. King’s “qualitative change in our souls” and “quantitative change in our lives.”

What does this look like in practice? Encouraging employers to offer flexible hours, work locations, and proactive commitments to retaining women in the workforce, including in leadership roles, will be vital. Also crucial are new models and approaches for equity in caregiving. It means that we’re not isolating, or “othering” people based on their religion, identity, geography, race, class, ability, or culture. It also means not exclusively choosing local, whether in our philanthropy or politics, when we are interconnected locally, nationally, regionally, and globally. Actions that increase a sense of separateness have profound consequences.

Also, there is a need for job programs that specifically focus on the needs of women. With many of the higher paid jobs of the future being in STEM fields, there must be a commitment to STEM equity given the barriers to girls’ access to STEM education and women’s access to STEM jobs, entrepreneurship opportunities, and leadership.

Politically, we need a global campaign to support more female candidates for political office at local and national levels. At times of crisis, the gains made by the women’s movement are rapidly unwound. We need to support women’s political voice in parliaments and formal institutions, as well as women leading grassroots movements for change.

Boards and leaders of organizations need to commit to gender equity in their structures as much as in their programs. This also means ensuring these structures have real power and funds to advance gender equality and social inclusion.

A few weeks ago, I moderated a panel on gender lens and social inclusion investing in a time of COVID that was co-presented by The Asia Foundation and Philanthropy New Zealand. There was so much wisdom from the panel. Melanie R. Brown, Senior Program Officer at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, said, “If you remember nothing else, remember this: Inside a racist, sexist, patriarchal system philanthropy has to be in active resistance.” She also said, “We must co-create systems where we all belong … [And so] in your organization, think about the systems and beliefs that lead to devaluing black, brown, Indigenous women, and people. Do you have processes in place that include honoring lived experience? Are you acting with a sense of urgency against the tide of incremental change?”

Sarah Haack Byrd, Executive Director, Women Moving Millions said, “We need to embrace an intentional intersectional approach that is inclusive of gender, race, and class. Grantmaking needs to reflect this complexity.” Draw on the combined creativity, connections, and resources of a philanthropic movement to be a bold and sustained funder for a gender-equal world.

PEAK Grantmaking recently asked its members a couple of questions. The first question was “What would you dare to do if you could decide where $100 million of your organization’s funding goes?” Responses included: give it all to multi-year general operating grants with minimal reporting; give it to cooperatives and the people they serve; fund grassroots organizations doing amazing work; provide long term funding streams to support leaders of color, and increase support for policy and advocacy work.

The other important question that PEAK Grantmaking asked its members was, “What bold move do you wish your organization would make but is too cautious to make?” The responses were revealing, and the answer I most liked was Stop funding issues and topics and start funding movements, leaders, and communities.

I would say to all donors, including private sector donors: Continue to fund women’s organizations, networks, and movements working to address gender-based violence, including the nexus between gender-based violence and women’s economic empowerment. And fund independent journalists who are exposing the issues around gender-based violence and speaking out bravely and boldly, such Fatima Bhojani, the author of “When I Step Outside, I Step Into a Country of Men Who Stare.”

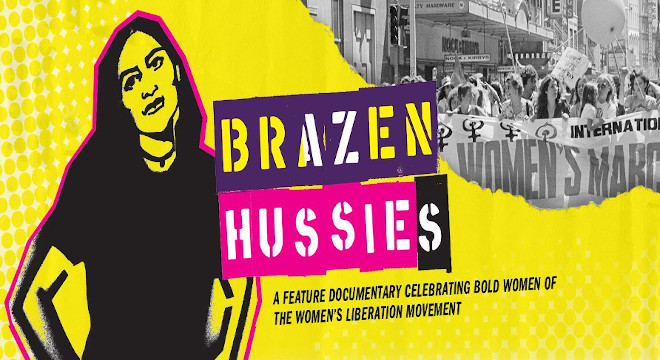

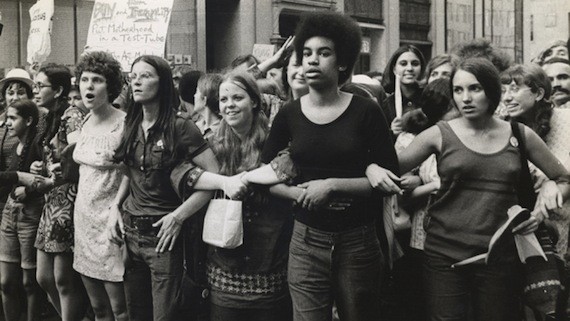

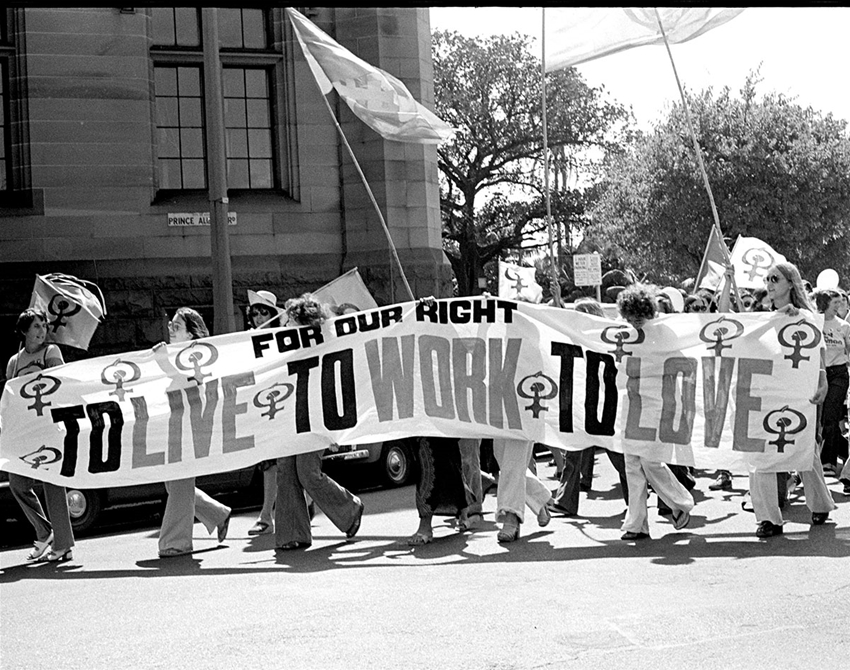

Recently, I watched the films She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry (about the birth and rise of the women’s liberation and feminist movements in the US from the late 1960s) and Brazen Hussies (about the emergence of the women’s liberation and feminist movements in Australia from the late 1960s). What struck me about both these films was the fearlessness, creativity, imagination, and courage of the many female leaders and coalitions that led to important advocacy for change.

These films capture some of the sheroes of our time out there on the frontlines. Susan Brownmiller: “Change happens because radicals force it.” The indomitable Bella Abzug: “We’re going to see that there’s a liberation not just of women but of men too.” Virginia Whitehill: “You’re not allowed to retire from women’s issues. You still have to pay attention ’cause somebody’s going to try to yank the rug out from under you, and that’s what’s happening now.”

Writing about those who are trying to “yank the rug,” John A. Powell said, “There’s no healthy side of the color/othering line. Slavery and racism injured both the slaveholder and the enslaved, but not in the same way. Patriarchy injures and distorts both male and female life, but not in the same way. These injuries and distortions also occur at the institutional, structural, and cultural levels. . . . If we can lean into belonging in the most powerful and loving way, it is possible for rapid change to happen in a relatively short period of time…This requires us to engage ourselves and the other…in the spiritual and the material. And, not at a safe distance, but with intimacy and love…As we build bridges and even become bridges, we will be doing a service to the world…”

There is a traditional Ubuntu saying, I am because we are that invokes the opportunity to create a beloved community from the inside out. As Resmaa Menakem has said, “We will not end white-body supremacy—or any form of human evil—by trying to tear it to pieces. Instead, we can offer people better ways to belong and better things to belong to.”

The beloved community is a concept that is grounded in love. In compassion, connection, the “I see you,” Buber’s “I and Thou.” It’s what I think about in relation to my parents and to the parents of many friends and colleagues in a time of COVID-19. About what is happening in the care community, in so many hospitals, nursing homes, people’s homes, refugee camps, urban streets, farms, conflict zones, slums, villages, and war zones across the globe.

My dad almost died twice in these last weeks. However, he came back and is fighting hard. I notice that there’s an expectation that people who are old and being cared for must remain submissive, grateful, and quiet rather than rattling the cage. Dad is not that person. Over many years, he’s been the person on the phone to his local member of parliament, the person writing a letter to ministers to advocate for change. Even in these last months, he’s retained a strong sense of his rights and what constitutes justice in caregiving. He refuses to be ‘othered’. It’s like a body blow to be denied the level of care and access to treatment that he believes is his right—that we should all believe is our right and our duty to defend and advocate for.

Instead of “othering” patients, colleagues of Oliver Sacks speak of how the neurologist and author “would imagine himself into them.” and ask “How are you? How do you be?” And through his questions, using narrative as therapy, patients were ‘storied back into the world.’ Oliver Sacks himself said, “Each of us is a singular narrative, which is constructed, continually, unconsciously, by, through, and in us—through our perceptions, our feelings, our thoughts, our actions; and..our discourse, our spoken narrations. Biologically, physiologically, we are not so different from each other; historically, as narratives—we are each of us unique.”

I feel a constant sadness and yet also such compassion and attunement to the suffering of others. And of course, I’m also buoyed by so many examples of the indomitable human spirit in the face of so many challenges. I also find myself celebrating even more deeply moments of joy now, recognizing they are precious and often fleeting.

I find joy in myriad ways. In my friend Hallie’s online qi gong lesson where we all lift chi up then pour chi down like a waterfall. In daily beach walks where dogs are skidding into the sea, giddy with the feel of spray and surf, where young women ride horses into the sea and seem like rocking horses in the ocean. In pulling out my sketchbooks to crayon feelings as much as figures in a rainbow of color. In tea ceremonies with my neighbor Heather, whom I never would have met if it hadn’t been for COVID. In cloud watching while lying on my back, doing stretches in the park. And of course, in any catch-up with friends.

Each Friday, late afternoon, I have my Zoom singing lesson with Australian singer-songwriter, Lucy Wise. It’s often the time that the kite surfers are out in full force on the ocean. As I’m facing the sea while singing, these beings—like human catapults—are flying across the water and upward in the air, buoyed by colorful kites that swoop the skies. It feels miraculous in these times, and it’s also a reminder that self-care is a political act—and that, as my friend Melanie R. Brown says, rest is revolutionary.