Credit: PeaceGovPH

Between 2000 and 2019, the United Nations Security Council adopted a series of ‘Women, Peace and Security’ resolutions – starting with United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 – that mandated the inclusion of women and their concerns into every stage of the peace process. The resolutions follow almost a century of women’s rights advocacy by national and international women’s organizations.

The 1325 resolutions are specifically intended for conflict and peace-building contexts. Importantly, they follow from the “human security” discourse at the United Nations since the mid-1990s, and as such, many of the mandates apply to other situations of acute insecurity — such as disasters and climate induced events, while expanding the scope of security to reflect diverse experiences.

UN Security Council Resolution 1325 and its sister resolutions are the product of several historical factors. First, decades of transnational activism, advocacy, and networking had brought the women’s movement significant experience in lobbying national delegations at the UN. Second, changes in the thinking about development and women’s roles in development had led to landmark women’s conferences in Mexico City, Nairobi, Copenhagen, and Beijing. Finally, as more feminists engaged academically, questions about women’s invisibility in international relations, and the failure to document and account for women’s experiences and work, began to be raised more often.

These three factors had the impact of broadening the understanding of ‘security’ and making it imperative for the international community to acknowledge that women’s experiences in conflict were different and significant.

Despite the vibrancy of the women’s movement in Asia, not all governments in the region are willing and interested in implementing the mandates that are core to advancing the Women, Peace and Security agenda. Further, the varying levels of progress and commitment can potentially impede outcomes.

Credit: John Teo NewStraitsTimes

What is critical in all of this is the role that civil society organizations are playing in advocating for progress on the Women, Peace and Security agenda and mobilizing social movements on the ground to advance women’s role in peacemaking and peacekeeping. When grassroots women take the lead, they ensure transparency, strengthen democratic decision-making and contribute to inclusive development.

Mindanao in the Philippines is an example of this in practice, as I observed from my recent trip there.

“This is an historic moment,” my colleague, Noraida Chio, Senior Program Officer said to me excitedly soon after I arrived. “It’s the first time these women senior combatants have traveled to a meeting such as this with an international NGO, after 48 years in the struggle.”

Credit: Mindanao Times

Credit: BIWAB

We were in Cotabato City in Mindanao, Philippines waiting with anticipation, seated at bench seats in a small café with a few people scattered at other tables. Soon after, several of the women officers from the Philippine Bangsamoro Islamic Women’s Auxiliary Brigade (BIWAB) arrived. One with her husband in tow, who sat smiling and watching us from a nearby table while we talked.

We ordered plates of food for the women, hungry from their over five-hour trip to meet with us. Then we talk. These former combatants have known nothing but civil war for the last few decades, with many becoming child soldiers at the age of eight or nine years old. “It was a choice of becoming a soldier, or becoming a victim,” says one woman. “The massacres were beyond anything you could comprehend.”

Credit: Insamer

Today, the BIWAB has over 10,000 women members including over 300 war widows. They’ve now formed the League of Moro Women organization with 33 branches across Mindanao so that they can actively, within a new era of self-determination, shape peace for their communities and country. “As a result of what we have been through, we can organize for peace and prosperity for our women,” said one of the BIWAB members with us.

I was in Cotabato City in Mindanao, Southern Philippines, spending time with Noraida together with another colleague, Aisha Midtanggal, Program Officer, to learn more about the pivotal role that over 50,000 women had played in leading the peace process, to secure a lasting peace there. Now, women were being seen as the best chance of maintaining this peace. Ensuring their continued access to economic opportunities and their active role in the transition government is vital for the time ahead.

For those not familiar with the history, on 15 October 2012, a preliminary peace agreement was signed in the Malacañan Palace between the Moro Islamic Liberation Front and the Government of the Philippines. This was the Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro, which called for the creation of an autonomous political entity. The signing came at the end of 32 peace talks between the two parties, over a nine-year period.

Credit: UNHCR Mindanao

In July 2018, President Duterte signed into law the creation of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), providing a new opportunity for shattered communities to rebuild after five decades of violence. After 21 years of peace negotiations there’s finally a reason for hope and optimism for building a lasting foundation for peace in the Bangsamoro.

Credit: The New Humanitarian

The Bangsamoro region in central and western Mindanao is, over recent decades, the least economically developed, with the lowest rates of formal employment, the highest unemployment, the lowest rates of banking access, and the lowest household incomes. It has also had the highest rates of conflict and violence, with 40% of households experiencing displacement, and 10% of households displaced more than five times in a decade. Within this environment women have been the most economically marginalized, often excluded from access to education and training, finance, and business opportunities.

Credit: Al Jazeera

Governance in the region has been historically weak, more akin to a ‘hollow State’ than a functioning State. This has meant there’s little data or support for women entrepreneurs to address structural barriers inhibiting their success. Anecdotal evidence suggests that women-owned businesses in the Bangsamoro are overwhelmingly micro-enterprises concentrated in agriculture, food production, textiles and other handicrafts. Challenges include access to finance, buyers, markets, and networks.

Noraida, herself a Bangsamoro woman, encouraged by our country representative, Sam Chittick, has supported women’s sustained leadership in the peace process in Mindanao. This has included supporting a coalition of 32 women’s organizations as part of the Women Organizations Movement for the Bangsamoro (WOMB). This has resulted in women organizing horizontally across religious and faith-based lines using The Asia Foundation’s training in ‘Thinking and Working Politically’ to find commonality of message and approach. The women knew they needed to create a diverse movement across religions and faith to build lasting peace.

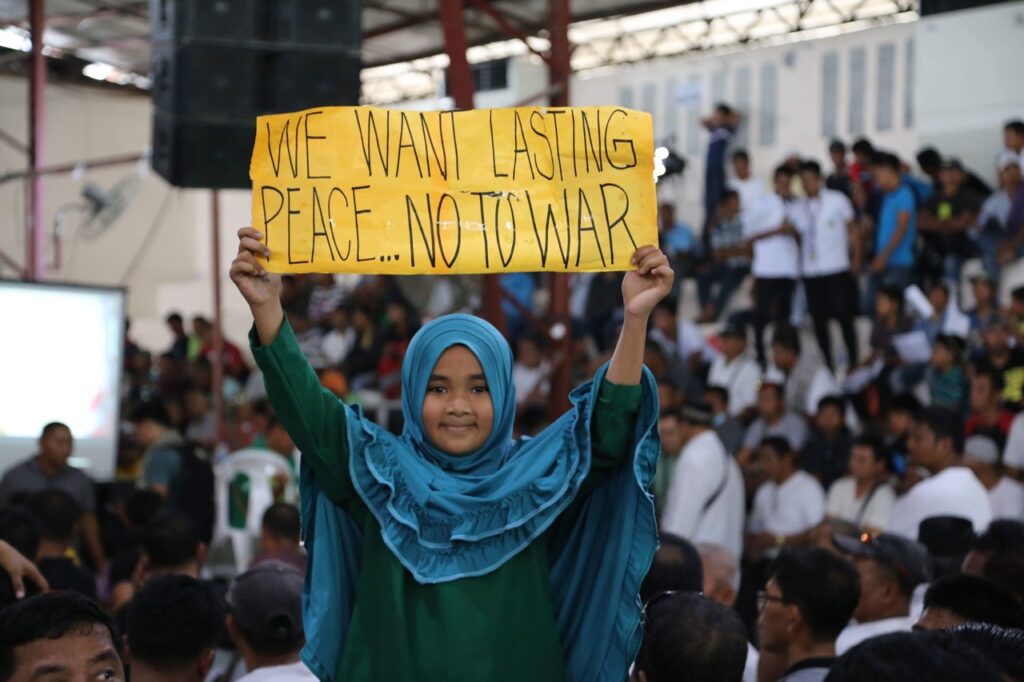

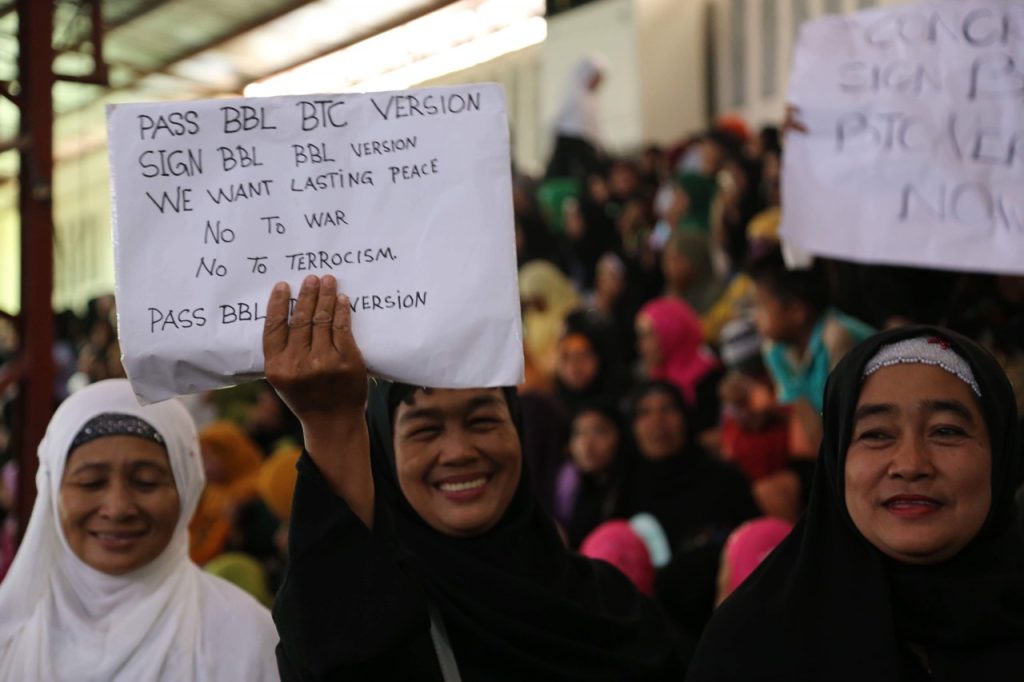

Credit: Filmmaking for peace, International Alert

Then, adopting a ‘train the trainer’ system, these women trained thousands more women to organize vertically, to influence policy makers and politicians in committing to a new peace accord and autonomy for Mindanao. In the end, over 50,000 women unified in the political arena to lead a strong movement focused on the ratification of the Bangsamoro Organic Law to enable the formal establishment of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao. The women represented civil society organization representatives, government employees, religious leaders, parliamentary representatives, teachers, madrasah administrators and owners, and business owners. These WOMB members have their own significant networks – for instance one WOMB member, the Society of Empowered Royal Ladies, is connected to over 50,000 women.

When we meet some of the WOMB members, they’re clear about their priorities. They recognize the importance of supporting women economically as much as politically. This includes supporting women to access training to start their own businesses and connect to markets. We discuss the idea of a Bangsamoro Women’s Business Center to provide training to emerging and current women entrepreneurs, including using technology to access buyers, markets, supply chains, peer learning and networking. The women say this business center would support people buying locally too – “if we want to get something, we get it through the community.” Such a center would help counter women going abroad for work and would help reduce poverty and inequality. With Islamic banks opening in the region there’s an opportunity to involve them in supporting women entrepreneurs to grow their businesses.

We inform the WOMB members that there’s interest from impact investors in creating a distinctive Bangsamoro brand. This would mean that consumers could purchase products from a Bangsamoro range and, in so doing, know they’re also giving women the best chance to sustain peace in the region through a strong economic buffer and foundation. The women are excited by the potential and talk about the option of Bangsamoro branded products such as coffee, turmeric, bananas, rice, local delicacies, silk, weaving, dried fish and licorice to sell to markets.

Credit: UNHCR

Coupled with this support for women’s access to economic opportunities and security in Mindanao is the equally important need to support their political voice and leadership. We head across town to meet with some women who have strong views on what’s needed.

We meet with MP Bainon Karon, Chair, Regional Commission on Bangsamoro Women (RCBW) and Helen Rojas, her Chief of Staff, together with a group of women they’ve invited to join us. They’re committed to sustaining women’s active participation in this transition process and beyond, including ensuring that women are involved at all levels of government. Assisting this process is the fact that the Philippine government has a Magna Carta of Women, dedicating at least 5% of national budget for Gender and Development programs and initiatives. In addition, the local government code has a Seal of Local Good Governance, that recognizes where women are active in key decision-making processes. What’s important, these women say, is to ensure women represent the diversity of the population and not just from politically influential clans.

We discuss the idea of a ‘Stronger Together’ community awareness program to educate the local community about better outcomes being achieved when women and men work together as parliamentarians. This would be the precursor to a campaign to support more women candidates for political office. In light of the success that women’s parliamentary networks have had in other countries as a solidarity network for women in politics and parliaments, we imagine the creation of a Bangsamoro Women’s Parliamentary Network. A solidarity network to support peer exchanges, mutual learning and connection to women parliamentarians and networks in other countries including visitations.

We hear from the women about the importance of supporting women as voters and monitoring women’s participation in the 2022 elections through a Women’s Situation Room. The women discuss an integrated approach to elevating and amplifying women’s political participation by reducing barriers and increasing opportunities to support political parties to nominate more female candidates.

Froilyn Mendoza – credit Conciliation Resources

Ensuring those who are the most marginalized have the opportunity to participate in political processes is crucial. This means paying attention to the voice and views of Indigenous women in Mindanao. Froilyn Mendoza is the Executive Director of Teduray Lambangian Women’s Organization and she shares with us the challenges of representation for the five indigenous tribes in BARMM, comprising some 120,000 people and 2% of the population. Many families retain traditional roles and experience high rates of poverty and illiteracy. Health issues are a major concern, including high rates of maternal mortality due to the influence of pesticides and chemicals on crops and lack of food nutrition. While children may receive primary education, they often don’t receive any secondary education due to their contributing to farm labor. Women farmers require advice on crops, diversification, and access to buyers and markets to support them to increase to their income and thus ensure better education and health outcomes for their children.

Credit: Mindanews

In a keynote address at the Australasian Aid conference recently, Radhika Coomaraswamy, former Under-Secretary General of the United Nations and Special Representative for Children and Armed Conflict said, “There is a real need to look at post conflict recovery in a more creative way and see how we develop post-conflict areas quickly and dramatically. …Most importantly, programs should aim at tapping the initiatives, creativity and resourcefulness of the local population as well as imparting skills with regard to the latest technology… The WPS agenda will get no traction in Asia unless it deals with livelihoods and post-conflict economic and social recovery with the same enthusiasm we have for women’s representation and accountability for sexual violence.”

We visit MP, Susana Anayatin, one of only 13 women in Parliament out of 80 Parliamentarians. She’s also the only Christian woman MP with the remainder being Muslim. While women are better represented at local government level as mayors and governors, they’re a minority in Parliament.

Susana says, “A focus on food production is essential, as so many women farmers are living in poverty. There’s an opportunity for these women to produce Halal products for export to Muslim countries. With the conflict resulting in so many widows and orphans, we need to address the basic needs of these families. I’ve introduced a Bill for economic and psycho-social support for widows and orphans. This will also reduce the potential for extremism as a result of grief, anger and despair as fallout from war.”

Credit: Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process

In her keynote speech, Dr Coomaraswamy addressed the issue of violent extremism: “Unless we speak honestly and unless we are firm in proactively adopting a women’s rights and a human rights perspective on violent extremism and counter terrorism, we will no longer be a cutting-edge agenda either regionally or globally. Women’s groups can play a major role in defining a new discourse that understands the very serious security concerns but also helps preserve human rights, human security and our humanity. We must set that as one of our major goals and priorities.”

I comment to Susana and Noraida that often domestic violence and other forms of violence increase or remain high, even after peace agreements are signed, if there hasn’t been an intentional focus on supporting combatants to understand what is triggering violent behavior and feelings. Susana agrees, “Cycles of violence will continue if we’re not able to stem the potential for violence of the next generation. For as long as there’s a feeling of victimhood and belittling, there’s no healing, and there will always be violence.”

Susana is also focused on the role of education in promoting peace and giving students the chance to break out of a cycle of poverty. Students in the BARMM are required to undertake Arabic and Quranic studies either at a Madrasa school (Islamic school) or a public school. Currently teachers at Madrasa schools receive much lower salaries than public school teachers which fuels resentment and polarizes poverty and inequalities. There are moves to upgrade Madrasa schools and to ensure parity of salary for all teachers. In addition, there’s a strong push to upgrade and institutionalize all Madrasa schools so that they are accredited with approved curriculum and a required standard of teaching in all subjects. At present, 90% of students are male at Madrasa schools. Some students go to Madrasa schools five days a week and others attend a public school during the week and a Madrasa school on weekends.

Before we leave, I ask Susana if she feels confident that things will change for women with this transition government. She pauses and then says, “My heart is filled with hope and prayers.”

Noraida, Aisha, and I visit the Bangsamoro Museum. We walk inside – to a wall of male governors at the entrance to the Museum. While there are images of women as weavers and textile artists, there aren’t any photos depicting women’s political participation and contribution to the peace process. “We need a Women’s Memory Project to permanently capture the vital role Bangsamoro women have played in the peace process,” I say. “A visual and voice capture through oral history and visual documentation.” We add this to the ideas for a comprehensive approach to supporting women’s political participation and representation in Mindanao.

We visit another woman whom we hope can be honored in the future for her role in the transition government. Atty Elijah Dumama-Alba is the young and energetic Attorney General and she’s in charge of drafting the administrative code for this transition government. She’s also a former Asian Development Fellow with The Asia Foundation. I ask her how she secured the important A-G role. “I was supported by a great male mentor, and being an Asian Development Fellow also provided valuable professional development opportunities to position me for this work. Now I’m given a lot of work due to parliamentary colleagues seeing me as competent and efficient. I really hope more women will be able to join me in this transition government.”

For women to play active economic and political roles, they also need to be able to confront the trauma they’ve experienced.

Moroproneurs was established in 2016 to support women entrepreneurs and to also help them deal with the trauma they’ve lived through. El-ham Tiboron Edza is a staff member of Moropreneurs which is currently supporting 32 women social entrepreneurs and 80 youth led enterprises. Elham is studying psychology so she can become a mental health specialist. I ask her about the psycho-social support networks currently available to people here. “There are few psychologists available to provide psycho-social support to communities and little infrastructure such as hotlines to support people who are continuing to experience mental distress, suicidal or violent tendencies, or depression,” Elham says. This is also part of the network of services the transition government needs to build to support people so they can function again and actively contribute to this newly established autonomous region.

Credit: Mindanews

After two days spent with those involved in the transitional government and grass roots advocacy to secure long-term peace and stability in the region, I depart. We have a plan to secure funding for women’s political participation and economic empowerment. I leave with our commitment to get more funds to those grassroots organizations who are playing a crucial role to create a vibrant, just, and equitable Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao. If more than 50,000 women can organize to lead a peace process, imagine what’s possible if they’re given the voice, resources, and influence to transform an entire region. Like Susana, I’m filled with hope. Patti Smith’s optimistic protest song “People have the Power” plays in my head.

Credit: CatholicSun Keith Bangcoco, Reuters