Coronavirus is upending people’s lives in myriad and layered ways. This includes the impact on frontline health workers, caregivers and those needing care. We’ve had to figure things out with family, friends, work colleagues, and with our wider community and networks. And we’re still figuring things out as the shapeshifting effects of the virus continue to play out.

A month ago my brother and I helped our parents go into residential care on the cusp of a Coronavirus lockdown. It was a new place and one that met their needs. This included their having a shared bedroom and another room as a living area. However, the manager of the care facility introduced new measures the day our parents moved in, requiring our parents to have their beds in separate rooms, and thus to be separated each evening. The day after the move I wasn’t allowed to see our parents due to further restrictions in place that deemed my visit non-essential. Dad had a sense of urgency in his voice when he asked if we could visit. It was heartbreaking to have to say we weren’t allowed. “Your Mum and I want to be together during this twilight time,” my Dad said on the phone, desperation in his voice.

While I was in the foyer of the care facility speaking on the phone with my Dad, an elderly woman who looked worn out, was resting on her walking stick in the reception area. She’d placed her husband in respite care so she could have a break from caring for him. The woman was saying to the receptionist that she’d have to take her husband home again, as his mental anguish at not seeing her would be worse than the physical strain of her caring for him at this time.

The day after this phone exchange, the facility went into lockdown and our Mum stopped eating and our Dad’s health declined rapidly with the mental strain of their not being able to be together in the evenings, not have visitors, or even meet other residents. Our parents had to stay in their rooms except at mealtimes, where tables were spaced to keep residents separated.

We wrote to the head of the care facility about the severe physical and mental distress our parents were experiencing, including being separated at night after 58 years together. Our long letter documenting their experience resulted in its head office acting swiftly to move our parents to a new care facility where they could be together and have the level of professional and clinical care they needed. But not before our Dad suffered from lack of oxygen due to the clinical staff not monitoring his oxygen levels. He was disoriented and slurring his words the night before they were relocated and in a bad way by the time they entered the new facility. We were able to see our parents at the admissions area but couldn’t accompany them into the facility due to the continuing lockdown.

Our parents are now settled, are recovering from the trauma and are relatively happy. They’re lucky – they survived, they’re safe, and are well looked after now. However, I continue to wonder about the COVID-19 restrictive requirement in many residential care facilities, that denies residents all contact with family and friends, and the mental distress of many elderly people, especially those suffering dementia. There have been many accounts across the globe of family members not being able to say goodbye to loved ones due to Coronavirus restrictions, and of those with dementia being acutely distressed and traumatized before dying, and others thinking they’d been abandoned without knowing the situation. Dying alone is one of the cruel realities of Coronavirus. A nuanced, ethical approach to balancing risk with mental health needs seems critical in situations such as this.

Meanwhile, during this same time, one of my oldest friends, Paul, aged 54, contracted COVID-19 in New York. His Facebook posts went from reporting a mild cough to it getting worse, to him reporting being surrounded by nurses and doctors wearing masks to…silence. Facebook lit up with friends seeking information and worried posts. Then one of Paul’s work colleagues shared with us that he was in an artificial coma, intubated, that it didn’t look good. A frenzy of Facebook posts trying to get further information. I called the hospital and after several calls a nurse answers. “I can’t really speak to you, since you’re not family,” she said. “But I can say he’ll pull through.”

We all celebrate when Paul leaves the hospital eleven days later, conscious that the fight isn’t over. He’s weak, he’s isolated, he likely has massive medical costs, even with insurance, he can’t travel to be with close friends or family, and he’s working in an industry (tourism) that has all but shut down. Yet, with indomitable will and a lot of love and zinging energy from his global family, he survived.

And while all this is going on, my work at The Asia Foundation, goes into overdrive to respond to the impacts of Coronavirus across Asia where we work. My team and I quickly create a COVID-19 Lotus Rapid Response Fund to address the immediate needs of women and girls during the pandemic by getting resources where they’re most needed. This includes responding to the dramatic rise in gender-based violence and child abuse as lockdowns and restricted movement exacerbate unequal power relations and heighten economic and mental health pressures.

Domestic violence hotlines are developing ways to safely give women passwords for them to use in pharmacies or on the phone, or ways to communicate that they’re in danger when the perpetrator is so often in the same place. Finding ways to support women and children to be safe while giving them access to funds to sustain them economically is critical. We talk constantly about flattening the curve of Coronavirus infection. We need to focus as much attention on flattening the curve of domestic violence as it’s more deadly, corrosive and widespread than the virus itself.

There are many gendered impacts of COVID-19. Women’s loss of economic security as workers and entrepreneurs, including in the informal and gig economies and increased health risks to women on the frontlines of pandemic response as health and community workers, where they comprise between 70% to 90% of workers. Here they often face mental health issues as a result of caring for acutely ill COVID-19 patients, whilst also having to care for family, or having to isolate if the risk is too great due to their health work. These workers are at further risk due to many not having properly fitted masks since many are made for men and thus are too big for many women, as documented by Caroline Criado in her book, Invisible Women. There’s also the increased unpaid care work for women, including childcare, homeschooling, and eldercare. While more women are exposed to COVID-19, men are at greater risk of dying, leaving more women-headed households to manage through the crisis, often with fewer resources.

With women at the frontlines of Coronavirus response, ensuring that they’re contributing to policies and actions to respond to the situation is vital. More needs to be done to support grassroots women leaders and those working in community health to be part of decision-making on COVID-19 response and recovery and to amplify their diverse voices and leadership. This doesn’t seem to be happening much at present at a grassroots level, so we need to do more to make this happen.

To date, our rapid response fund has supported domestic violence hotlines and services in several countries in Asia, including counselling, emergency supplies, and referrals. We’ve helped construction of new handwashing stations in Timor Leste to encourage effective sanitation and hygiene practices. In Laos and Cambodia, we provided young women students with computers, internet credit, food and health supplies, and online mentorship to ensure their continued learning. In Cambodia, we’re supplying female waste collectors with masks, gloves, handwashing soap, first aid kits, food supplies, and educational kits for their children. In Indonesia, we’re helping women with disabilities and other vulnerabilities to start vegetable gardens, so they have access to fresh foods during the pandemic. In Pakistan, we supported the distribution of hygiene kits and in Cambodia and Malaysia, we’re assisting women entrepreneurs to transition their businesses online to access buyers and markets.

Of course, beyond the immediate response, there’s a growing list of what’s needed in the medium term. I’m conscious that we need to support women’s groups, networks, and movements to sustain this work, as much as to hold ground on important gains already secured to advance women’s rights. This means getting core funds to these groups and networks so that they can manage through this crisis.

Here in Adelaide, where I’m staying until I can safely return to San Francisco, I’m in a place at the edge of sand dunes and the sea. On weekends people fly kites or they kite sled across the water. I have a mermaid shell that my friend Jane found for me and left on my doorstep, and the other day I found another. The beach here is wild and largely empty. A man walking past, at a suitable social distance, called out to me, “Look at the water, see the dolphins playing!” Just at that moment, one flipped up. Pure joy.

And then there’s the birdsong, as continuous lullaby.

Other days it’s back to my favorite hobby, watching dogs loping and leaping across the sand, and then running full tilt into the sea. I dream of one day having a global assignment of doing nothing but photographing those bounding dogs and their love affair with the sea. I share their joy and their shaggy enthusiasm for everything beachy . My friend, Maxine, shared with me a clip made by Tilda Swinton of her four dogs leaping through the waves to the sound of one of Handel’s, ‘Rompo i lacci’, from his opera Flavio.

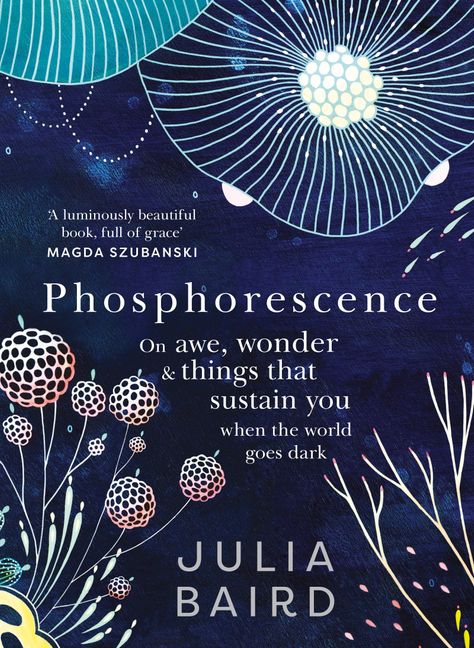

Each week I buy fresh roses and arrange them with my other ritual objects. I seem to crave beauty at present. And nature in all its forms. I think of Rachel Carson and her books about the sea, how much I learnt from them. It shouldn’t surprise me then to pick up a book called Phosphorescence: on awe, wonder and things that sustain you when the world goes dark by Julia Baird, where she writes about Rachel Carson and her own connection with the sea and phosphorescence. Baird writes about the phenomenon, ‘My fingers threw out fistfuls of sequins with every stroke. A galaxy of stars flew past my goggles. It was as though I was flying through space… gliding rapidly through a universe only I could see.’

Nature brings me back from the edge, and other times takes me to that wild edge. A sliver of sunset appears in the sky and before long it’s flooded in tangerines and pinks. I walk along the beach, navigating clumps of seaweed, children making sturdy sandcastles, and dogs variously sauntering, skidding, and skedaddling across the sand. While I was driving back from collecting supplies for my parents’, I was driving along a busy suburban road, and then suddenly I was on the main road heading to the beach. The scent of the sea seemed to infuse my car as I headed (hurtled) toward the sea, so primal was the call of the ocean.

I wonder which way the world will tilt. Will it be in recognition that we all breathe the same air, as COVID-19 has reminded us in such a stark way. Or will we amplify demonization of ‘the other’ and resort to increased tribalism and nationalism at precisely the time when there’s a window for a new world being possible, as writer and activist, Arundhati Roy, has opined. I plug into communities of philanthropists, philosophers, and activists (sometimes all three as one) who are thinking about a new Marshall Plan that might embrace such proposals as universal basic income, global health care, education for all, and a Robin Hood tax. Also a dramatic shift in power, patriarchy, and gender norms to eliminate violence and advance equality, an infusion of funding for the arts in recognition of its ability to transform individuals and societies, and a feminist Green New Deal. Oh, and the rise of community support networks and new democratic structures.

What would it look like if our working hours reduced, if there was work for all who need it, a rebalancing of caregiving responsibilities, and a dramatic reduction in our carbon footprint while giving us time to appreciate life on this blue ball, our earth home?

I’m listening to Radio Lab on Radio National to their Dispatch on Shared Immunity.

The presenters on this program, Jad Abumrad and Molly Webster, are discussing people who have had Coronavirus being able to donate their plasma because they have immunity after having the virus – they have a kind of superpower. Molly Webster then interviews Dr. Tatiana Prowell, an internist and medical oncologist at Johns Hopkins in the United States who had tweeted a request for plasma to support the 83-year-old father of her brother-in-law. They discuss the phenomenal response she receives from so many people wanting to give, who send images as well as messages to signal their intent to help.

“Why are you so hopeful?” Molly asks Dr. Prowell. She responds by saying anyone who is an oncologist of a certain age has cause to be deeply optimistic with the advances we’ve made in cancer treatment and the opportunity to save lives. And we will, here too. And the other reason is that it didn’t take long for Coronavirus to become a pandemic and thus it meant that with so many people infected there was a large pool of people who could donate plasma. Dr. Prowell goes on to say, “The thing about the plasma is that each transfusion of blood plasma can treat three people. And the coronavirus also infects, on average, three people (as compared to the Spanish Flu which was two). So there’s a symmetry in the universe and I feel there’s something beautiful about that.”

On Radio Lab, Jad comments, “As a paradigm, it’s such an interesting, intimate way to treat … it’s one person having suffered and survived then turning to the next person who is a few days behind them suffering and saying, ‘Let me help you.’ There’s something very spiritual in a way about that.”

Molly agrees, saying plasma is profound, that it’s about sharing immunity. “We can pass on immunity to another as protection. You can shepherd someone. You can offer them safe passage… saying “I’m spiritually holding your hand, I’m helping you walk this path, make this journey.”

It reminds me of the words of Leonard Cohen when he wrote to his great love and muse, Marianne Ihlen, as she was dying, “Know that I am so close behind you that if you stretch out your hand, I think you can reach mine… Endless love, see you down the road.”

That love is reciprocal, it can be the love of one giving plasma to another down the road to give them life, or it can be the love of one following in the wake of another close to death. Or something else again. Coronavirus is teaching us about love, as much as about inequality and immunity and what is essential in our lives. If we can use this time to reimagine the world and what is needed, then we will have come through fire and the alchemic process will have begun.

2 Responses

Jane,

I am happy to learn your parents are in the same bedroom.

I send you light.

Seeing Tilda Swinton’s dogs dance to Handel’s glorious music-pure magic.

Birmingham awaits your return.

Much love,

Thanks dear Nancy, it will be gorgeous to catch up again and I really do look forward to getting to Birmingham this year to see you. Much love from Australia Janexxx