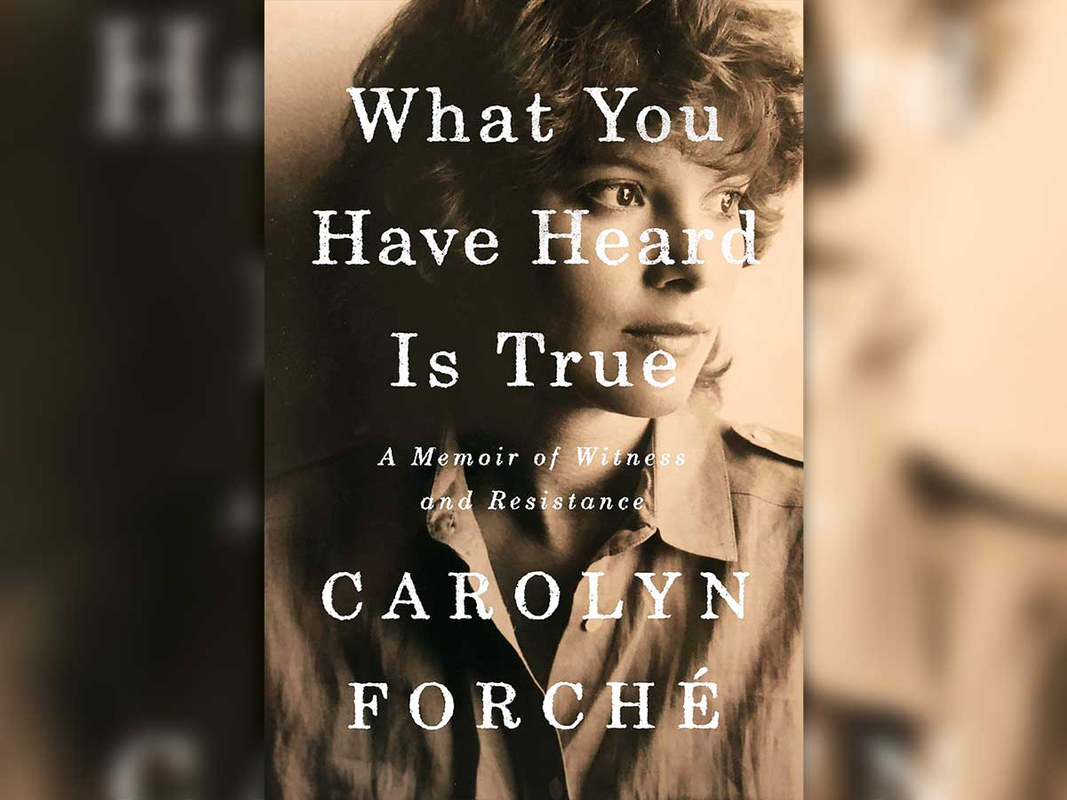

What You Have Heard is True by Carolyn Forché

Anything I write about this book will be inadequate in conveying how profoundly Carolyn Forché’s writing, experiences and language affected me. It’s a strange thing to write that I felt this was a book speaking to me, and for me. I got what she was saying, and she got me by writing it. I first encountered Forché when I was doing my MA in Peace and Conflict Studies and studying the poetry of witness, which defines Forché’s life’s work as a poet.

Her book, Against Forgetting was an electrifying concept and experience. This book takes that idea to another level in embodying what it means to live a life of constant remembrance with its reminder of what’s at stake.

The stories in this book about Forché’s time in El Salvador, still one of the most violent countries in the world, with her revolutionary guide, Leonel Gómez Vides, demand time and presence. As she said of him, ‘It was as if he had stood me squarely before the world, removed the blindfold and ordered me to open my eyes.’ It took Forché some 15 years to write this book and, in reading it, I can understand why. Toward the end it’s also about her kinetic connection with the war photographer, Harry Mattison, who documented the devastation of El Salvador and whom she agrees to marry just weeks after they meet. I read the book slowly because I wanted to understand how evil is sustained and the role poets can play in a moral call to act. This is the journey Forché takes us on in this luminous, devastating book. Book of the year. Hands down.

Forché some 15 years to write this book and, in reading it, I can understand why. Toward the end it’s also about her kinetic connection with the war photographer, Harry Mattison, who documented the devastation of El Salvador and whom she agrees to marry just weeks after they meet. I read the book slowly because I wanted to understand how evil is sustained and the role poets can play in a moral call to act. This is the journey Forché takes us on in this luminous, devastating book. Book of the year. Hands down.

Call Them by Their True Names: American Crises (and Essays) by Rebecca Solnit

In this new collection by Rebecca Solnit her focus is on revolutionary storytelling in these revolutionary times. She explains this when she says: ‘Part of the job of a great storyteller is to examine the stories that underlie the story you’re assigned, maybe to make them visible and sometimes to break us free of them. Break the story. Breaking is a creative act as much as making, in this kind of writing…. There are stories about the inevitability of capitalism, stories that there are two sides to the reality of climate change, a host of stories that don’t get told because they rock the boat, discomfort the powerful, unsettle the status quo. Those are the stories that will make you wildly unpopular with some people it’s great to be wildly unpopular with – and beloved by others it’s even greater to be beloved by…’

In this new collection by Rebecca Solnit her focus is on revolutionary storytelling in these revolutionary times. She explains this when she says: ‘Part of the job of a great storyteller is to examine the stories that underlie the story you’re assigned, maybe to make them visible and sometimes to break us free of them. Break the story. Breaking is a creative act as much as making, in this kind of writing…. There are stories about the inevitability of capitalism, stories that there are two sides to the reality of climate change, a host of stories that don’t get told because they rock the boat, discomfort the powerful, unsettle the status quo. Those are the stories that will make you wildly unpopular with some people it’s great to be wildly unpopular with – and beloved by others it’s even greater to be beloved by…’

Inherent in this book, and in so much of Solnit’s writing is the importance of thinking and working politically. As Solnit says, ‘Politics is how we tell the stories we live by: how we decide if we value the health and well-being of children, or not; the autonomy of women’s bodies and equality of our lives, or not; if we protect the Dreamers who came here as small children, or not; if we act on climate change, or not. Voting is far from the only way but is a key way we shape the national narrative.’

Solnit invokes us to use our individual and collective power to focus on what’s important, including a burning planet. She calls us to use our story making and breaking power to change the course of history. Rebecca Solnit is an icon writer, feminist, human rights advocate to many of us. This collection is another reason why.

Salt on Your Tongue: Women and the Sea by Charlotte Runcie

Runcie’s connection to the sea forms on a childhood holiday to the Isle of Skye. The experience of sea and shore is one that captivates her and later, in her 20s and at a time when she is anticipating adventures at sea and on land, she instead becomes pregnant. Her pregnancy becomes a very different adventure as she uses this time to explore history and stories of the sea and how it connects us to culture, art, love and life.

Hearth: A Global Conversation on Community, Identity and Place edited by Annick Smith and Susan O’Connor

The word ‘hearth’ is both comforting and captivating as the title and focus of this book as it suggests a place of rest, renewal and return. In this anthology of poetry, prose and photography, writers explore their own association with hearth at a time of flux and flow due to climate change, migration, conflict, and the impact of technology and globalism.

The word ‘hearth’ is both comforting and captivating as the title and focus of this book as it suggests a place of rest, renewal and return. In this anthology of poetry, prose and photography, writers explore their own association with hearth at a time of flux and flow due to climate change, migration, conflict, and the impact of technology and globalism.

In The Rent Not Paid by Kavery Nambisan she writes, ‘The primitive desire to nestle for warmth and love is persistent, untiring…I cannot think of any other place I would rather be than this, a village in my beloved Kodagu. I have the security of home, closeness to nature, the trust and love of my people. But a question gnaws at my happiness: If all of this is mine, why is it so? My good fortune troubles me as much as it fulfills. Why should my husband and I have complete authority over a piece of land while millions in my own country are homeless?’

In Heaarth, (yes, it’s really spelt this way!) environmentalist Bill McKibben talks about community and introspection at a campfire.

In A Tea Ceremony for Public Lands by Terry Tempest Williams and Sarah Hedden, the setting for the story is ‘Castle Valley…a small desert hamlet in southern Utah…a community that values starlit nights and solitude, a town of self-described recluses, renegades, and ruffians in the respectable form of teachers, architects, gardeners, environmentalists, militia men, peaceniks, wine-makers, goat-herders, artists, writers, photographers, and retired oilmen, potash workers, and entrepreneurs.’ It’s a description I love as some of it could apply to where I live, in Sausalito.

My favorite piece is called A Staircase with a View by Ameena Hussein, a Sri Lankan writer. It affected me so much that I read it twice more. I won’t quote here as I hope you’ll find your own copy to read.

This anthology is itself a source of comfort, meditative and provocative in its exploration of what gives life meaning.

When Women Were Birds: Fifty-Four Variations on Voice by Terry Tempest Williams – Re-read

“I am leaving you all my journals, but you must promise me you won’t look at them until after I’m gone.” This is what Terry Tempest Williams’s mother, the matriarch of a large Mormon clan in northern Utah, told her a week before she died. Williams was stunned to discover that her mother had kept journals. And then she was shocked to find that all three shelves of journals were blank. In fifty-four short chapters, Williams recounts memories of her mother, considers her own faith, and the idea of absence as much as the presence and meaning of art and voice.

“I am leaving you all my journals, but you must promise me you won’t look at them until after I’m gone.” This is what Terry Tempest Williams’s mother, the matriarch of a large Mormon clan in northern Utah, told her a week before she died. Williams was stunned to discover that her mother had kept journals. And then she was shocked to find that all three shelves of journals were blank. In fifty-four short chapters, Williams recounts memories of her mother, considers her own faith, and the idea of absence as much as the presence and meaning of art and voice.

The title, When Women Were Birds, brings to my mind the sculptors living along the Sepik River in Papua New Guinea, who would sculpt women’s bodies with bird beaks on their faces. I was told it was a symbol of transformation. And so, I was drawn to this book many years ago for this offer of transformation, and I returned to it for the same reason. There is much wisdom in this book including the role of the arts in an activist life. Her writing is lyrical and deeply affirming, such as this: ‘And each night the smell of orange blossoms and sea salt ignited sunsets into flames slowly doused by the sea. Not year of my life has missed a baptism by ocean. Not one.’

Of course, first and foremost Williams is a storyteller. She shares the story of how she met her husband when one of her friends brought him into the bookshop where Terry Tempest was working. “My dream in life is to own all the Peterson field guides,” the man said passionately.

My friend looked at him and said, “That is the dumbest thing I have ever heard.”

Without thinking, I interrupted. “I already have them –”

Our eyes met. “Brooke Williams,” he said.

Importantly, Williams tells stories of the power of art to change the course of history. In response to a proposed Utah Public Lands Management Act of 1995 that would reduce protection of public lands from 22 million acres to 1.8 million acres Tempest mounts her own protest to politicians and policy makers. Getting nowhere, Terry Tempest Williams conceives Testimony, a series of essays and poems by some of the finest writers in the country. Senator Bill Bradley led the filibuster in The Senate by reading the contributions in the book and, as Williams shares, Testimony is now part of the Congressional record. in 1996 President Clinton designating the new Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, protecting nearly two million acres of wilderness in Utah.

Driving back from the ceremony (celebrating the new act to protect the lands) I felt like a sister to Thelma and Louise, seated in their light blue convertible with the arch of sky above me. Not quite an outlaw and not yet choosing to drive off a cliff, I was still free to move in big, open country that for now remained wild. Democracy demands we speak and act outrageously. We can change the world if our view is long and focused with friends drawn lovingly around the place we call home.

The Snow Leopard by Peter Matthiessen – Re-read (favorite)

A book of discovery, about self more than snow leopards, though there’s that too.

Field Notes From a Hidden City: An Urban Nature Diary by Esther Woolfson

Esther Woolfson is the author of one of my two most favorite books about birds, Corvus: A Life With Birds (the other one is H is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald). Field notes is an apt title for this book as it captures Woolfon’s everyday encounters with nature through the seasons and from the perspective of her urban home in Aberdeen. Crucially, in her storytelling Woolfson captures the loss of habitat for so many creatures as the consequence of not acting on climate change and due to the impact of rapid urbanization globally. “If we lose sparrows, everything will change. Our lives will change, even if we don’t at the time fully appreciate how… As with every loss, our lives will be thinner, lesser; the future not only of the physical but our mental world will be diminished, the world of our history and legend where the life of all cultures resonates with all we’ve seen and all we’ve lived with, plant and animal, stone and cloud.”

Walking in Wonder by John O’Donoghue: Eternal Wisdom for a Modern World

For those who have read and loved the bestseller, Anam Cara (the Gaelic phrase for soul friend) by the late John O’Donoghue, this is a great companion volume. This book is a distillation of O’Donoghue’s radio talks with his friend, John Quinn, a former broadcaster on Irish National Radio. Here O’Donoghue speaks of wonder as being a companion to compassion in our approach to life and to our actions that will make a difference. ‘Each day is a secret story woven around the radiant heart of wonder. The sacred duty of being an individual is to gradually learn how to live to awaken the eternal within you.’

O’Donoghue was a priest with a doctorate in philosophy and a fierce social justice advocate. For most of the 1990s, O’Donoghue lived in silence and solitude on the rocky coast of County Clare. He left the church around the time of the runaway success of Anam Cara, deciding he didn’t have a lot in common with hierarchy. In an obituary in The Guardian captured O’Donoghue’s humor and humanity:

“For a student of Hegel who had written his PhD in German, O’Donohue found it amusing that pop stars and presidents had his book at their bedside, that Hollywood directors and household name actors sought his counsel. It confirmed his view that there is an intersection between philosophy, poetry and theology which can host an audience increasingly exiled by what he called ‘the frightened functionaries of institutional religion.’ As an accomplished poet, he had the literary tools and dazzling vocabulary to speak a language that persuaded you he was right.”

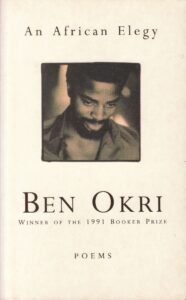

An African Elegy by Ben Okri – Re-read

This book of Ben Okri’s poetry has been a favorite of mine for many years. The poems are evocative and true. I was excited that Okri was speaking at Adelaide Writers’ Week this year but then I was so tired from all my travel I fell asleep instead. On waking I turned to YouTube to watch a speech Okri gave to the Kolkata Literary Festival in India and I pretended I was there, and he was talking to me. That’s how I feel about his poetry too. It’s up close and personal. Visceral, really. Okri says, ‘We’re born from stories, visible and invisible…I’m fascinated by the invisible ones.’ He goes on to say this:

‘All creativity starts with questions. And the quality of the questions we ask, as writers and as citizens, determines the quality of the discoveries we make about ourselves and about our societies. Question askers…are the most dangerous people in society. They are the most liberating people in society. The fight for justice is for everybody, for society… (But) the keenest fight for justice is for the most dispossessed, the poorest people in our society. Justice is not just about poverty, it’s about truth. Justice is about a way a society is run. Justice is about what a society takes to be its fundamental truths…We should be discoverers of possibilities and not concluders. We should not be full stops, semi-colons or even a dash. Only free people can make a free world.’