I’d wanted to go to Bangladesh ever since I heard the story of the sari shop with a secret door to a bookshop for women who wanted to read feminist books. The women would emerge from the change rooms to greet their husbands with books discreetly hidden under their saris. In joining The Asia Foundation, I finally got my chance to go to Bangladesh, and in the right role too as head of women’s empowerment.

I arrived in Dhaka, Bangladesh, to news that draft legislation to lower the age of marriage was under discussion. Bangladesh has one of the highest rates of child marriage in the world, and the highest rate in Asia. Fifty-two percent of girls marry before the age of 18, and 18 percent are married before they turn 15. This results in girls being denied an education and usually getting pregnant soon after being married with some dying in childbirth and others facing severe health issues, together with their babies.

In 2014, the Prime Minister pledged to end child marriage, committing to enact a tougher law that included severe punishment for child marriage, to having a national action plan to end child marriage under age 15 by 2021, and to end to all marriage before age 18 by 2041. Since then, no national action plan has emerged, and the proposed new law allows for child marriage in special circumstances such as accidental or unlawful pregnancy, and sets no minimum age for such marriages. With the new law, girls may also be forced to marry their own rapist if the ‘unlawful pregnancy’ clause stands.

Against this backdrop I spent time with our Bangladesh country representative and deputy, Hasan Mazumdar and Sara Taylor, together with the other staff in the Bangladesh office, to learn more about our programs there including our work in supporting young people’s engagement in their community. This is important at a time where young people are exposed to radicalizing forces, especially given the uptick in terrorism including the civilian attack on an upmarket bakery in Dhaka in July 2016. More than 20 people, mainly foreigners, were killed in this attack, for which ISIS claimed responsibility, as part of terrorist groups’ targeting of minority religious groups, foreigners, and those people who have different views to theirs. With ISIS also purported to have connections with local groups, there will likely be more such attacks in the time ahead and with the challenge that these threats are no longer just local in nature.

Against this backdrop I spent time with our Bangladesh country representative and deputy, Hasan Mazumdar and Sara Taylor, together with the other staff in the Bangladesh office, to learn more about our programs there including our work in supporting young people’s engagement in their community. This is important at a time where young people are exposed to radicalizing forces, especially given the uptick in terrorism including the civilian attack on an upmarket bakery in Dhaka in July 2016. More than 20 people, mainly foreigners, were killed in this attack, for which ISIS claimed responsibility, as part of terrorist groups’ targeting of minority religious groups, foreigners, and those people who have different views to theirs. With ISIS also purported to have connections with local groups, there will likely be more such attacks in the time ahead and with the challenge that these threats are no longer just local in nature.

The Bangladeshis who perpetrated the attack on the bakery had studied in elite schools and colleges, and came from affluent families. With ready access to the Internet they could easily be recruited, with encouragement from friends and perhaps with a heady and romantic attraction to heroism and adventure to fuel the cause.

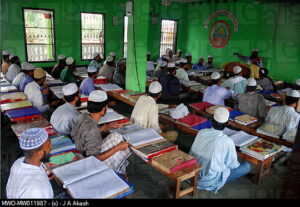

There is also the situation created by an increase in the number of “madrasas” (religious schools) mainly funded by Saudis. These schools focus on a specific religious (Islamic) curriculum and thus those graduating do so with a very defined worldview coupled with reduced chances of securing employment compared to students attending other schools. Students who attend non-religious schools often have better opportunities to be employed due to having education that better equips them for the job market. This combination of young people radicalized by a particular religious worldview, isolated from other perspectives and increasingly shut out of a competitive job market, creates a tinderbox situation awaiting a strike spark.

Some Bangladeshi students interviewed by the BBC’s Ethirajan Anbarasan claim that the attraction to radicalization is fueled by the loosening of family ties and the increasing separation of students from their families and communities, and a rising fascination and engagement with social media.  Here are the thoughts of four of those students interviewed:

Here are the thoughts of four of those students interviewed:

That’s the discussion that we are actually going through right now, how can we make youths more active, or create more inclusion among ourselves so that these sorts of distractions do [not tempt them]?

Most of the frustrated youth do not have an icon or a role model who they can follow and who can mentor them. Having a role model is important because then [one] can have a goal in life. We can try to emulate that person. Our life should always have a purpose, what [we] really want to be. When I was in school, there was a student organization linked to an Islamist party. They came to me and only said that they prayed five times a day. I knew that they were trying to brainwash me. Unfortunately, lots of my friends did not have that kind of awareness. Those people can be easily manipulated.

After the Gulshan <bakery> attack, I think that the youth community should be more connected. They should go and discuss their issues and inner feelings with their families and friends offline. We think that we have a separate world on social media like Facebook. But, actually, we are alone there. When we meet face to face, we get to know each other and we understand each other’s values. In our country, what we can do is to use our imams in mosques. They can spread good values to our youth more frequently during prayers. We [also] have to make sure that this right information is online.

I think what is happening in Bangladesh is misrepresentation and miscommunication about Islam and about religion. We know that Islam is a religion of peace.

The Asia Foundation has undertaken important work in supporting young people as agents of change and it will be critical to step up this focus in the time ahead. De-radicalization will only be possible by initiatives such as improving young people’s access to broad based education and pathways to employment, as well as to meeting spaces and public convenings where they are exposed to a diversity of views. We need to intentionally foster a commitment to conflict- resolving communities – something that my mentor, Dr. Stella Cornelius, spent most of her life working to promote.

Important here is the opportunity to create spaces for dialogue with students at the university in order to engage them in conversation about key issues. I joined Hasan Mazumdar, and staff member Saiful Islam, in a meeting with the Vice Chancellor of the University of Dhaka, Dr. Siddique. Saiful studied at the University of Dhaka and his pride and excitement was palpable during our drive toward the university.

Important here is the opportunity to create spaces for dialogue with students at the university in order to engage them in conversation about key issues. I joined Hasan Mazumdar, and staff member Saiful Islam, in a meeting with the Vice Chancellor of the University of Dhaka, Dr. Siddique. Saiful studied at the University of Dhaka and his pride and excitement was palpable during our drive toward the university.

Dr. Siddique is a distinguished leader and also a wonderful host. We discussed the university’s important role as a focal point of progressive and democratic movements after the Partition of India and as the oldest university in modern Bangladesh. In our time together I suggested that the university create a Bangladesh Peace  Prize modeled on the impressive Sydney Peace Prize created by Professor Stuart Rees and the Sydney Peace Foundation. This would provide an opportunity for the university build on its reputation for being at the forefront of independence and peace by recognizing those qualities in key individuals who have advanced peace in our time. We also discussed the prospect of staging some forums that provide an opportunity for engaging students in a dialogue on key issues facing the country and the region, especially in addressing conflict.

Prize modeled on the impressive Sydney Peace Prize created by Professor Stuart Rees and the Sydney Peace Foundation. This would provide an opportunity for the university build on its reputation for being at the forefront of independence and peace by recognizing those qualities in key individuals who have advanced peace in our time. We also discussed the prospect of staging some forums that provide an opportunity for engaging students in a dialogue on key issues facing the country and the region, especially in addressing conflict.

Neila Husain, a conflict and security analyst and former senior research fellow at the Bangladesh Institute of International and Strategic Studies, has made a compelling case for the need for micro-level peacebuilding:

Peacebuilding is often associated with the post-conflict restoration processes. While macro-level peacebuilding in post-conflict countries is undoubtedly important, we equally need micro-level peacebuilding in ‘peaceful’ countries where there is no classical war and yet innocent men, women and children are being killed, injured, raped, rendered homeless, and kidnapped every day.

This is where peacebuilding efforts can intervene to teach people tolerance, respecting others’ views and building their communities together. I believe a country like ours needs a multiple tier peacebuilding mechanism, which starts from the grassroots, family, school and community-level and goes all the way up to the top engaging policymakers, civil society and law enforcement and security agencies.

We should learn at an early age the importance and process of building peace in our community by engaging with local elites, youth, women and children by bringing them together. In the long run, we learn to communicate, listen, and voice our concerns through dialogue, not by force, violence or making threats. Peacebuilding should be a comprehensive and an all-inclusive process that is accessible to all.

Critical to this work of peacebuilding is to elevate women’s participation and leadership in conflict resolution and in economic and political life. Women currently occupy 20% of reserved seats in national parliaments in Bangladesh. In March 2016, The Asia Foundation released a survey on Bangladesh’s Democracy: According to its People. A large majority of Bangladeshis who responded to this survey (62%) think Parliament should have only or mostly male representatives, an opinion shared by both men (69%) and women (55%). The most commonly given reasons relate to men’s intellectual superiority to women (men know more, more intelligent, understand politics, better educated). Although the majority believe national government should be mostly for men, a strong majority (71%) support reserved seats for women.

Critical to this work of peacebuilding is to elevate women’s participation and leadership in conflict resolution and in economic and political life. Women currently occupy 20% of reserved seats in national parliaments in Bangladesh. In March 2016, The Asia Foundation released a survey on Bangladesh’s Democracy: According to its People. A large majority of Bangladeshis who responded to this survey (62%) think Parliament should have only or mostly male representatives, an opinion shared by both men (69%) and women (55%). The most commonly given reasons relate to men’s intellectual superiority to women (men know more, more intelligent, understand politics, better educated). Although the majority believe national government should be mostly for men, a strong majority (71%) support reserved seats for women.

Countering these attitudes and beliefs is critical, as is advancing policies and laws designed to increase women’s participation as voters and candidates. With national elections due by early January 2019, The Asia Foundation is preparing to again play an active role in getting more women on the electoral roll, voting and standing for election, and monitoring violence to ensure that women are able to vote safely. Shifting power and resources in support of women’s voice and participation is crucial.

Supporting women’s leadership in the labor force is also vital. For instance, Bangladesh is the 10th largest tea producing country and has 163 tea gardens with over 100,000 workers, 75% of whom are women although few occupy leadership roles. These workers earn very little, suffer poor nutrition, and lack knowledge and ability to exercise their rights, especially as they live in the tea gardens. The Asia Foundation is working to support labor rights through workshops that involve The Bangladesh Cha Sramik Union (BCSU) representing these workers, the Bangladesh Tea Association, which represents tea garden owners, officials from the Labor and Commerce Ministries, and experts together through moderated sessions intended to reduce barriers between these groups. This inclusive approach has started to shift workers’ and owners’ perceptions of each other’s actions and contributions in the tea sector. The Foundation has also supported worker awareness about the labor laws so that workers are aware of their rights and have the confidence to engage in collective bargaining.

From Dhaka I fly to Rangpur with my colleagues Nazrul Islam and Shabbir Shawkut. In 2007 The Asia Foundation undertook an assessment with Imams to determine the potential role of Imams in addressing the high rate of violence against women and the high rates of child marriage. The resulting program was designed to engage Imams in training where they study Koranic verses to understand that the Koran encourages men to behave well toward women rather than being violent and, further, to confront anyone who is perpetrating violence against women. The Asia Foundation engaged Imams and the Imams’ wives in a regular forum where this training was undertaken.

A group of these Imams, their wives and local women leaders have agreed to meet with us and to share more about what this training has meant for them and the kind of impact they’ve been able to have. My colleague Nazrul Islam convenes the meeting with Shabbir Shawkat providing invaluable interpreting skills and important insights.

The Imams and their wives speak of the importance of engaging Imams in other districts in order to expand this work to ensure women live free of violence. They share stories of how this training has informed their involvement and interventions in their local communities. One Imam tells the story of his brother, also an Imam, who used to beat his wife regularly and who stopped after the training.

The Imams and their wives speak of the importance of engaging Imams in other districts in order to expand this work to ensure women live free of violence. They share stories of how this training has informed their involvement and interventions in their local communities. One Imam tells the story of his brother, also an Imam, who used to beat his wife regularly and who stopped after the training.

Another Imam tells story of another Imam witnessing his mother being beaten senseless by his father for failing to have his dinner ready on time and that the neighbors stayed away until she was taken to the emergency section of the hospital. The Imam witnessing the violence vowed afterwards to never be a by-stander again and to commit to ending violence against women. The Imams speak of the power of talking in the mosques about addressing the violence and of the benefit of involving their wives in the training. One Imam says “I have to be accountable to my wife because she knows the verses in the Koran very well.” I ask the women present if they have noticed a difference. “It makes a difference for us when our husbands are supporting us to educate about women’s right to not be hit by a man,” says one woman.

A third Imams says, “If I interrupt the violence as an individual then people take it personally but if we act as a group then people see it as a social intervention. That’s where the power lies. Another Imam says that they have many constituents, and violence against women is pervasive in so many settings. Often even when the Imam intervenes, any action against the male falters at the village court level. That is why there is a need to scale up the training and extend it to Imams and their wives in other districts in order to have the level of impact needed as a genuine movement for change. The Imams say those who don’t have the training are quite ignorant about some of the Koranic texts and so educating them can make a positive difference.

I ask the Imams what they’re doing to discourage child marriage and the Imams say they do this through sermons where they speak of the need for girls to receive an education before marriage so that they can perform better in family and social life.

The Imams say they ask for birth certificates before approving a girl’s marriage and they say no if she is under age. Often fathers say they are forced to marry their daughters for reasons of security and honor (no pre-marital sex). Sometimes it’s the girls themselves who want to get out of their family home in order to express their sexuality, especially those living in rural areas where there is often only one room for families, and thus girls are socialized to sex early.

The Imams say they ask for birth certificates before approving a girl’s marriage and they say no if she is under age. Often fathers say they are forced to marry their daughters for reasons of security and honor (no pre-marital sex). Sometimes it’s the girls themselves who want to get out of their family home in order to express their sexuality, especially those living in rural areas where there is often only one room for families, and thus girls are socialized to sex early.

The Imam’s wives are more vocal in opposition to lowering the marriage age to 16 than the Imams who say they don’t agree with the proposed change to the law but they won’t oppose it. The Imams say it’s more effective to speak to parents about the health, nutrition and maturity concerns re early marriage in their sermons. The Imams’ wives say that once a woman is employed she is dignified, and obstacles can be confronted and overcome, so working to ensure that a girl is educated and has a pathway to employment rather than being married off early is critical.

I ask the Imams’ wives if they would like their own forum to come together separately and they unanimously agree. “If we can discuss these issues regularly rather than in occasional forums then it is a motivating factor to do more, including distributing literature to communities” says one woman. I then ask if we need to create a separate forum for mothers-in-law to come together too, given their influential role. The women are vigorous in their assent and share that mothers-in-law sometimes come to the Imam’s wives’ forum because “they want to know what we are doing.”

The women say it would help if mothers-in-law had a separate platform to address issues in relation to women’s rights, as there would be a different dynamic at play for mothers-in-law in having their own forum. The women say engaging mothers-in-law in this work is key since they usually take their son’s perspective and condone and encourage the beatings. These women say it’s also important to reduce conflict between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law and to encourage love, harmony and affection in order to achieve domestic peace and freedom from conflict. This conflict between mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law is often exacerbated by the limited understanding by mothers-in-laws of religious texts and their belief that men have the right to be violent toward their wives.

The women talk about the need to earn an income beyond supporting their freedom from violence. They say it would help if they could access funds to support small enterprises managed from women’s homes to make garments or produce for a business or company. For instance, by having sewing machines, seeds and poultry and linking this work to markets. These women need to work from home and on their land, and have access to buyers and markets, and in this way they will have the income to support their children’s education and health as well as their own needs.

The women speak of being conscious of local community attitudes – neighbors will criticize their engagement outside the home and husbands may get angry if their wives seek to work, so the outreach that Imams’ are doing to husbands is key. The most usual scenario is that if the family is extremely poor, then the husband appreciates the extra income a wife can generate. However, if they are more comfortably off, the husband sees his wife working as an assault on his manhood and pride.

The Asia Foundation has been supporting Women Chambers of Commerce in six districts, including women entrepreneurs seeking to use technology for online buyer platforms, and a mobile network as a peer-to-peer system for advice and support. These Women Chambers of Commerce are a key network supporting women to start and sustain their own businesses, and they are also working to get banks to comply with central banking regarding lending to women entrepreneurs so that women have the opportunity to access start-up capital, then the chamber provides training to these entrepreneurs. There are 10,000 members of these chambers in Bangladesh working to increase women’s engagement in the economic sphere from the current level of 34% participation. Connecting Imams’ wives to these Women Chambers of Commerce would help them extend their work to end violence against women toward economically empowering women, including those who are survivors of domestic violence.

The Asia Foundation has been supporting Women Chambers of Commerce in six districts, including women entrepreneurs seeking to use technology for online buyer platforms, and a mobile network as a peer-to-peer system for advice and support. These Women Chambers of Commerce are a key network supporting women to start and sustain their own businesses, and they are also working to get banks to comply with central banking regarding lending to women entrepreneurs so that women have the opportunity to access start-up capital, then the chamber provides training to these entrepreneurs. There are 10,000 members of these chambers in Bangladesh working to increase women’s engagement in the economic sphere from the current level of 34% participation. Connecting Imams’ wives to these Women Chambers of Commerce would help them extend their work to end violence against women toward economically empowering women, including those who are survivors of domestic violence.

As we are wrapping up our time together, one of the women tells the story of a woman who dreamed of returning to get a college education. At home, every time she talked about it her husband got angry and beat her and he continued to humiliate and dominate her in a myriad of ways. Then an Imam began calling at their home and having a series of quiet conversations with her husband. Slowly the woman noticed a change in her husband as he stopped hitting her and verbally abusing her. Finally, he agreed that she could return to study and later he would speak proudly of the fact that she had returned to college. Now this woman is graduating and is hoping to secure employment that will support her family as well as help her to reach her own potential. “This is the change that is possible with such interventions,” says the woman.

We leave the community feeling excited by the potential in the time ahead, and assuring them that we will do all we can to attract the funds and support to continue and expand this important work. I farewell the staff in Bangladesh inspired by their level of their commitment and all that has been achieved to date.

Next stop Indonesia…

Back on my boat storms roll in and the waves get big. I’m close to the elements as the last little boat on the dock before the sea. With wind and water lashing I wonder whether my boat will break free of its chains and carry me to sea. Instead, a new day breaks with blue skies and the return of bobbing sea lions as welcome company.

My friend, Tony, took some pics of me here and sent them to ‘Jane and her floating contraption’. A floating contraption sounds a little like Chitty Chitty Bang Bang when Chitty floats on the water and perhaps that’s the point. Like the Chittymobile there’s a kind of magic I feel every time I step into my boat and draw on the deeply joyful energy within. With this kind of infusion, I really feel like we can change the world – the power of movements in all their diversity are shaking the world and people power is rising.

My friend, Tony, took some pics of me here and sent them to ‘Jane and her floating contraption’. A floating contraption sounds a little like Chitty Chitty Bang Bang when Chitty floats on the water and perhaps that’s the point. Like the Chittymobile there’s a kind of magic I feel every time I step into my boat and draw on the deeply joyful energy within. With this kind of infusion, I really feel like we can change the world – the power of movements in all their diversity are shaking the world and people power is rising.

There is a power that can be created out of pent-up indignation, courage, and the inspiration of a common cause, and if enough people put their minds and bodies into that cause, they can win. It is a phenomenon recorded again and against in the history of popular movements against injustice all over the world.”

― Howard Zinn, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train: A Personal History of Our Times

Jane Sloane

Dhaka

One Response

Thank you for this beautiful, inspiring, thought provoking report! (I’m a high school friend of Josh Gordon.)